This blog is supported in part by my Patreon. You can help support content like this by pledging a monthly donation.

Gone Home is an amazing work. Yes, it’s a bit sappy and its ending is a bit pleasant and optimistic, but screw that. “Sentimentality, empathy, and being too soft should not be seen as weaknesses.” Gone Home is sweet, although certainly not sickeningly so; it is the sweet of a “sour” candy where the sour sanding soon fades away.

I’m writing about a single cabinet in the game. This one:

This cabinet is the first meaningful interaction in the game. You start in a dark, covered porch in a rainstorm. The front door is locked and bears an ominous note from your younger sister Sam: “We’ll see each other again someday. Don’t be worried.” There are four interactibles available at the start of the game: the locked door, a meaningless cup, the goose-neck lamp on the cabinet, and the cabinet doors.

Fumbling in the Dark

Interestingly, the lamp on the cabinet begins the game turned off. This seems contrary to the received wisdom of level design: use light to guide the player. In this case, having the light begin lit would draw the your eye and encourage you to interact with the cabinet. With this guidance specifically absent, you are more likely to fumble around, unsure what to do.

However, this “fumbling” serves a didactic purpose. This is the first room in the game, and it is a handy location to let you get used to the controls. Gone Home, as a game about relationships and family, is likely to appeal to people unused to video games, so these people might require more time and practice to acclimatize themselves to the controls. The porch is a small space with clear landmarks (the lit front door and the protruding external door, which emits the sound of rain) where the player can wander around without getting lost. There are no significant objects above eye level, mitigating some inexperienced players’ tendency to look down toward the floor and miss elevated features.

The unlit lamp also enhances verisimilitude. The porch light is on, which makes sense: Sam is expecting Katie’s arrival via airport shuttle. However, there is no reason for the goose-neck lamp to be on; its intended purpose seems to be to enable reading in the nearby chair, and even in the mid-90s setting of the game the family (with a park ranger mother) would be environmentally conscious enough to not leave that lamp on when not in use.

Finally, turning on the lamp introduces an action that you will do again and again in the rest of the game. The house starts with most of its lights off, and part of the exploration and discovery process is finding and turning on light switches to facilitate more exploration. Requiring you to turn this light on to clearly see the contents of the cabinet teaches this behavior in the previously-discussed safe and contained space of the porch.

The Doors

The cabinet has two doors on its front; the left one starts slightly ajar. This serves to draw the eye even in the darkness. The porch area is covered in horizontal lines: clapboard siding, wainscoting, windowsills, muntins, and wooden chair slats. The slightly diagonal line of the ajar door stands out among these lines and the gap around it forms a stark, dark, inverted “L.” Should you turn the lamp on, the upper edges of the doors are highlighted and easier to see.

When you approach the cabinet, if you look down toward the cabinet doors, you see action text: “Open door.” This mirrors the text shown on the more prominent (and locked) front door, implying that these objects are equivalent and perhaps equal in their importance to progress. Opening doors is also something you will do a lot in Gone Home, and making the first door you can open be a small cabinet correctly implies that searching side spaces and containers will be very important in this game.

Interactible objects in the game also “grab” your mouse to encourage you to use them. When the cursor at the center of the screen (and thus your view) is pointed at an interactible object, your mouse sensitivity is noticeably reduced. Moving the mouse a set distance on your desk will move the view/cursor a smaller distance in the world than usual. This makes these objects feel “sticky,” because it takes extra physical effort to move the cursor away from them. Because of this, you are more likely to notice the doors and their interaction text if you’re examining them visually. When you sweep your view across the scene it seems to “stop” on the doors as if drawn by a magnet.

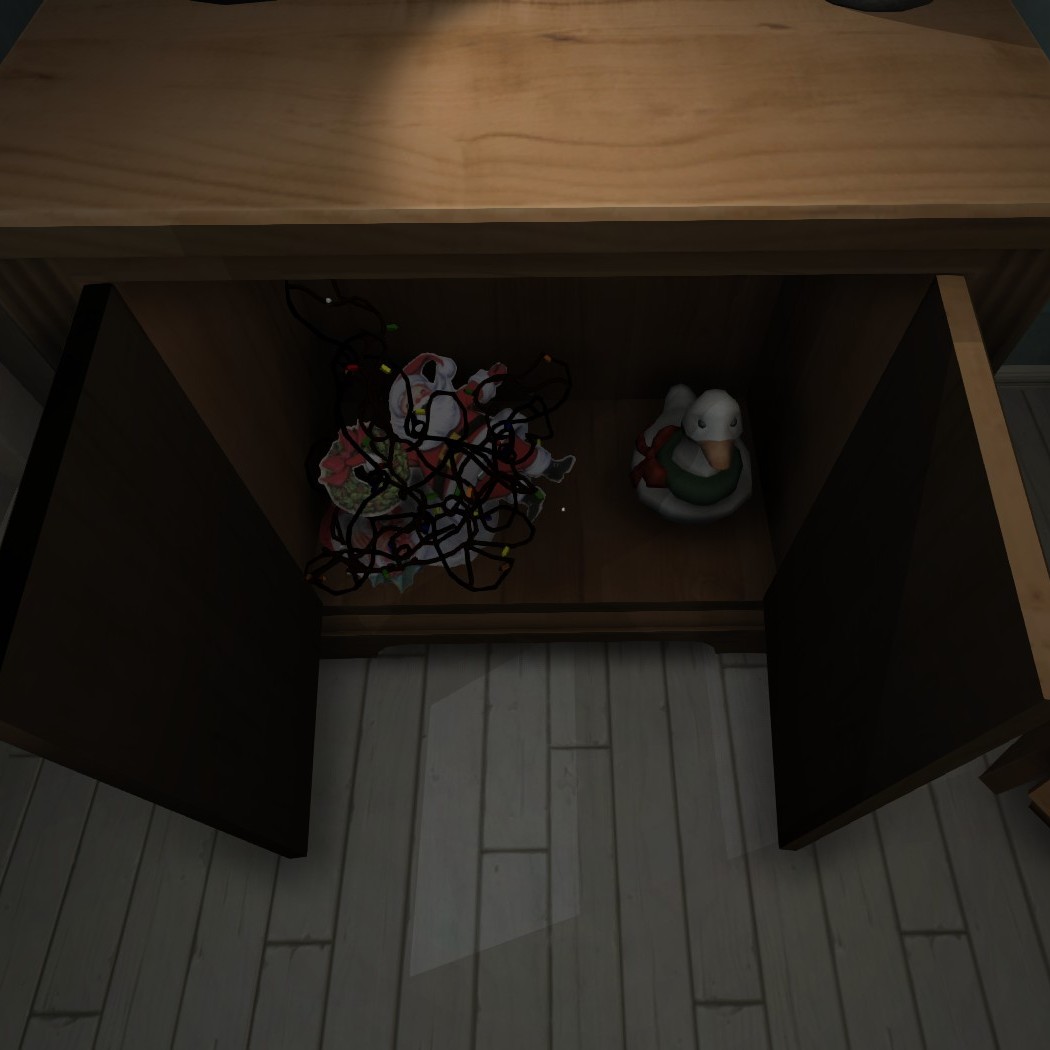

Since one door is ajar, you can see through the gap into the inside of the cabinet and catch a glimpse of the contents, which makes it more clear that the cabinet has an inside at all. The other furniture on the porch is static, and the luggage in the middle of the room can’t be opened. Players used to video games without robust implementation of household furniture might assume that the cabinet is scenery rather than prop, and never consider that it might open. However, with one door ajar, you’re encouraged to envision the cabinet as a container rather than as decoration.

Opening either door doesn’t reveal all of the cabinet’s contents; you see half of them, but the other half peek out from behind the other door. This encourages you to open both doors, reinforcing that doors are to be opened and cabinets are to be searched. Also note that closing the doors again at first seems to close them fully. However, while the left door does close nearly all the way (in contrast to its starting state, which is ajar by several inches) it still protrudes slightly when compared to the right door. This serves as a reminder should you open and close the doors again without properly examining their contents.

Christmassy Contents

Once you open the doors, you reveal the cabinet’s contents. On the left side of the cabinet is a tangle of Christmas lights, twisted up with a few cardboard Santas. On the right side is Christmas Duck, a festive duck decoration that, when picked up, reveals the key to the front door.

This tangle of Christmas decorations is, I think, the first bit of the bittersweet homeyness that pervades the game. Remember, Katie has never been to this house, but the decorations are surely familiar; families tend to use the same decorations year after year. You, the player, are likely to be a bit surprised by seeing such a minor and evocative detail in a video game. Likewise, Katie is likely shocked by seeing decorations she remembers from her childhood recontextualized in this new and alien place. As with many details of the cabinet, this pattern of childhood objects in a strange place continues throughout the game.

The new Greenbriar home is a sprawling mansion. There aren’t nearly enough lights in the cabinet to decorate the face of the house, and the lights that are there are very tangled. At some point Sam probably rooted through them, reappropriating many of them for use in her attic darkroom, which is lit by strings of red lights. Even taking those into account, there don’t seem to be enough lights, but I’m inclined to attribute that to the game’s necessary abstraction of details, like the absence of shoes in the house.

Christmas holds significance in the timeline of Gone Home. The gameplay takes place in June 1995, but the previous Christmas was a significant turning point in each subplot of the backstory. Sam had recently begun her secret romance, but had not yet learned of its impending deadline or exposed it to her parents’ disapproval. The seeds had been sown for the parents’ own marital discord, but that conflict had not yet come to a head. Katie’s father had reached the low point in his career and had not yet received the letter than would turn it around.

Holidays serve as a powerful symbol in the formation of a home’s identity. These Christmas decorations, which have already been used once at the new home when Katie finds them, served to assist the new Greenbriar house from “the new house” to a new home. Katie was abroad and wasn’t present for that transformation. To her, these are the old Christmas decorations from her childhood with no association to the new house, while to the rest of the family they have become linked with the new house and their new circumstances. Given the complicated fallout of the Christmas situation, the decorations likely hold mixed feelings for the rest of the Greenbriar family, but Katie does not yet know this context when you first see the lights.

Good Ol’ Christmas Duck

In order to progress in the game, you must pick up Christmas Duck to reveal the front door key beneath it. Christmas Duck is a ceramic duck wearing a Christmas scarf. Its glazing is cracked, suggesting either cheap construction or heavy use. There is a simple price sticker marked “$5.99” on the bottom, suggesting that it was purchased at a non-chain store or rummage sale. This is consistent with the Greenbriar family’s means: the father is a writer and consumer reviewer, while the mother is a government employee. They have the right level of income to buy an inexpensive but charming decoration and keep it well-loved for years.

The developer commentary node nearby explains that Christmas Duck is a recreated model inspired by an asset from the Unity Asset Store, but I’ve been unable to find the original model. It may no longer be available. (Edit: Steve Gaynor, designer of the game, reported on Twitter that the original Christmas Duck was actually from Turbosquid [webcitation].)

The key to the front door is under Christmas Duck. It’s common practice in suburban households to hide a spare door key in a theoretically clever place: under a doormat or rock, for example. This gives a way in if a family member forgets their keys or comes home to find the house unexpectedly empty. Katie may expect to be able to find a hidden key; she grew up with this family. However, it’s likely that the previous Greenbriar home didn’t have a porch large enough to contain a cabinet, so she’s unfamiliar with this particular hiding location. There is synergy between the player’s lack of knowledge and Katie’s lack of knowledge. Both know that the key should be somewhere nearby, but neither know exactly where.

Christmas Duck is a surprisingly complex object. It has a number of properties that are rare in the game. First, its name changes after you interact with it. When you first hover over it, it displays the text “Grab Christmas Duck.” However, after putting it down, the hover text changes to “Good ol’ Christmas Duck.” This verifies that Katie is familiar with the Duck and regards it with wry nostalgia.

Next, Christmas Duck has multiple home locations. It initially sits on top of the front door key. However, the game’s “Put Back” system lets you return objects to their proper place. In that linked article, Steve Gaynor says that being unable to keep the house neat would make the player feel like a “clumsy vandal:” picking things up, examining them, and tossing them on the floor. Instead, virtually all objects have a hotspot that lets you keep things neat. In the case of Christmas Duck, however, this location is not the Duck’s original position. After Putting Back the Duck, it sits to the left of the key, leaving the key exposed and available for interaction.

This serves two purposes. The first is to make it less likely that you’ll miss the key. If you pick up the duck and put it back without noticing the key, you still have a chance to spot the key (now beside the duck) in subsequent searching. The second purpose is purely practical. When holding an object, you can’t interact with another one, so it is impossible to pick up the front door key while holding the Duck. If you try, by positioning your cursor over the key and clicking, the first click puts the duck back and you can then click again to take the key. If the Duck returned to its starting location, clicking repeatedly would just set the duck down and pick it up again.

The Christmas Duck is, perhaps, unique in the game by having two Put Back locations. The first is here in the cabinet, but the second is near the end of the game in a wreath-like nest in the attic. The developer commentary nodes at each location explain that this is to reward the player for regarding the Duck as a companion and carrying it with you throughout the game. The presence of the nest in the attic is consistent with Sam using it as a container to carry Christmas lights upstairs, leaving the Duck behind to fulfill its new duties. However, if you carry Christmas Duck upstairs, the interaction prompt to place it in the nest reads “There you go, Christmas Duck.” Katie recognizes the nest as Christmas Duck’s “home” and places it there, further personifying it.

Maybe the title and story of Gone Home was actually about Christmas Duck all along.

The First Cabinet

This cabinet lives in a strange, liminal space. The enclosed porch, common in the northern US, serves as a place neither outside nor inside; it’s sheltered from the elements but provides a view of the surrounding landscape. There are weather-proof porch chairs but the windows don’t seem to open and the external porch door is heavy and wooden. The cabinet, with its lamp plugged into the nearby electrical outlet, is clearly a piece of interior furniture but here it serves as an exterior container for outdoor decorations. Just as the cabinet sits in an antechamber in the game’s fiction, so it serves the game purpose of a tutorial, guiding you from the exterior world of your desktop to the interior world of the sprawling game geography.

In order to play Gone Home you must open the cabinet and learn what it has to teach you.

I’m part of Future Proof Games. We’ve released the dark dialogue-based satire Ossuary and are working on Exploit: Zero Day, a social cyberpunk puzzle game currently in closed Alpha testing.

Words cannot express how much I enjoyed reading this. My hat off to you, good sir, for an amazing piece.

Thank you! I really enjoy close reading, and I’d like to do it more.