I haven’t addressed roleplaying games directly on Ludus Novus much. At first glance, they don’t fit in with video games all that well, and several times I’ve used them as a contrast to video games. However, there’s a distinction that I can make that I think makes them seem less distant.

When people say “roleplaying game,” they are usually referring to a rules system, often combined with a setting. To be clear, I’m referring to “tabletop” or “LARP” roleplaying games here. Dungeons and Dragons. Cthulhu Live. Traveller. Each of these seems so much broader than, say, Half-Life 2. While HL2 only offers one storyline, D&D is limited only by the Game Master and players’ imaginations. However, I think that a better analogue for a video game would be a roleplaying campaign.

I’ve run my short “one-shot” campaign, “The Dead of Apartment 4C,” three times. Each time, a different set of players has run through roughly the same plotline, just like each person who plays Half-Life 2 experiences the same potential narrative. The campaign uses the Fudge system for its rules, and I as Game Master have been the referee. For Half-Life 2, the Source engine is its rule system, and the player’s computer or console is the referee. Roleplaying games and video games look a lot more similar when we match a video game title to a roleplaying campaign rather than a system.

After the break, I’ll do a quick runthrough of some of the RPG theory I’ve picked up.

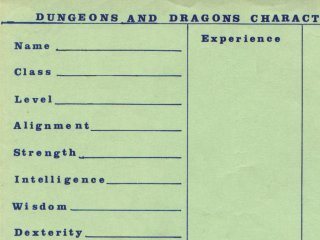

In its traditional form, the roleplaying game campaign is a collaborative narrative created by a group of people, with one person in the role of Game Master and the rest in the role of players. Each player controls a character in the game world. The Game Master describes the world, decides the precise result of player character actions, and controls all non-player characters. Both the GM and the players use dice to add an element of chance to events.

This is only the traditional form, though. The only part of that description not subject to change is the definition of an RPG campaign as a collaborative narrative. Everything else differs from system to system and from group to group. Independent RPG creators tend to be the ones pushing the boundaries, and the most popular online gathering place for them is The Forge.

The moderator of The Forge, Ron Edwards, has done an incredible amount of work to attempt to define and analyze the roleplaying game. Out of the Threefold Model, which divides RPG gameplay into Drama, Game, and Simulation, he created the GNS Theory, which describes three essential behaviors of RPG players: Gamism, Narrativism, and Simulationism. Finally, he created the definitively-named Big Model which subdivides and defines the experience of an RPG to a dizzying level of detail. I’m not sure the Big Model is entirely complete or concise, but it is interesting to look at, and it has relevance to all forms of interactive entertainment.

Fundamentally, though, the majority of RPG gameplay seems to take place in the traditional mode. A Game Master either acquires or invents a setting and potential narrative, and players each create characters to play through it. The essential difference between tabletop RPGs and video games is that video games almost universally isolate the player from the author of the work. If a video game developer can respond directly to a player, it is usually in the form of a sequel, expansion, or content pack that is fundamentally asynchronous. The Game Master, however, can change the game on a whim in response to her players, even modifying individual statistics in mid-battle to better suit the play experience. It’s a fundamentally synchronous form of interactive entertainment, and thus its authorship is almost always more personal and social than video game development.

One thought on “Character Sheets: An RPG Primer”

Comments are closed.