The other night, I picked up Gaijin Games’s Bit.Trip Runner for WiiWare. This game is the best example of pure, brilliant game design that I’ve seen in a good while. This is the game designer as teacher and leader; it’s what Anna Anthropy calls design as sadism:

As a designer and as a domme, I want the person who submits to me to suffer and to struggle but ultimately to endure: I challenge her while simultaneously guiding her through that challenge. The rules of the game and the level design carry that idea.

Runner does this through the gradual layering of new game elements, high challenge with low punishment, and optional bonus goals. Most of all, though, it guides through repetition. This is a game about rhythm, after all. For my favorite example of this, let’s look at a single measure of rhythm from the game, no longer than 2 seconds, that appears everywhere.

Watch the beginning of the above video to see the first ten seconds of level 2-11: “Watcher’s Watch.” Did you catch the repetition? This segment repeats the same sequence of level elements twice, and each sequence is in turn made up of two identical rhythms. It’s the “doot dee-doot,” the “one, and-three” rhythm that plays four times in a row at the beginning of the clip. This rhythm is found throughout the game. Most notable here, though, is that the lines in these two matching couplets require identical actions from the player, despite using different obstacles to evoke those actions.

Confused? Here’s a sketch of the first measure of the level, with a stream, a high fireball, and another stream:

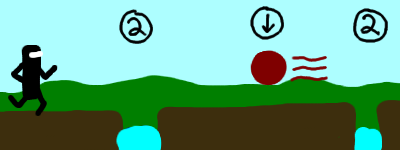

And here’s the second measure, with a rock, a high fireball, and a low fireball:

In each case, the player’s actions are the same, as indicated by the buttons in the images: jump, pause, slide, and quickly jump. These two situations look totally different in the level, but they require the same buttons to be pressed in the same rhythm. The first is more forgiving, as being a bit late jumping a stream is acceptable, while rocks and fireballs are death on contact.

What the game designer is saying here, through the medium of the game, is “Try this. Okay, now the same thing, but harder.” This repeats one more time: “Good job. Now, again… and one more time.” The level then moves on, and ten seconds later returns to the exact same sequence: “Remember this? Do it again.” Repetition builds on repetition; this rhythm appears a total of eight times in this level, and must be performed perfectly each time in order for the player to succeed.

This rhythm, along with countless others, appears again and again in the game. Sometimes, it’s made up of only fireballs, of UFOs (fireballs’ level one equivalent), or of rocks and crystals (which call for jump-jump-kick instead of jump-slide-jump). This repetition, this reuse of rhythms, serves to divide up and direct the game’s extreme difficulty; each complex level is made up of discrete chunks that repeat within the level as well as echo rhythms from earlier levels. Only rarely is a new rhythm or game element introduced, which gives the player time to learn and digest each addition.

There’s a clear conversation between the designer of Runner and the player. The designer presents an impossible-seeming level, and promises, “You can defeat this. Trust me.” The player then tries and fails and tries again, and in doing so begins to recognize the elements that make up the level, learned in earlier lessons. It’s notable that there is no mockery here. Getting hit doesn’t make the player character explode, or cause a loud noise, or make sad music. It just whisks the character back to the beginning of the level. “Failure is okay,” the designer says. “You’ll get it one of these times.”

Completely not adding to the conversation here, but your drawings are very cute.

I suppose this is one reason why rhythm games are (were?) popular, though they certainly did include quite a bit of mockery. DDR and Dance Maniax in particular have fairly condenscending announcer tracks that (I imagine) turn some people off.