Sparky’s Den, in the Memorial Union at Arizona State University, is a bowling alley and arcade where I spent many of my summer late afternoons as a young teenager. I can’t find any photos of their arcade online, so I don’t know if they still have the old Dungeons and Dragons or Alien vs. Predator beat-em-ups, the Gauntlet Legends machine, the copy of Silent Scope.

Sparky’s Den, in the Memorial Union at Arizona State University, is a bowling alley and arcade where I spent many of my summer late afternoons as a young teenager. I can’t find any photos of their arcade online, so I don’t know if they still have the old Dungeons and Dragons or Alien vs. Predator beat-em-ups, the Gauntlet Legends machine, the copy of Silent Scope.

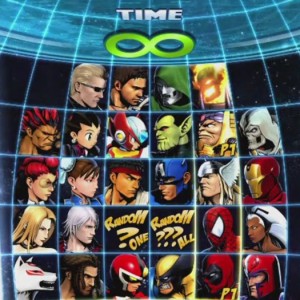

The Marvel vs. Capcom machine.

I don’t have the same love of fighting games and arcades that a lot of video game folks seem to. I was never good at split-second reflexes, and my arcade time was limited to short spans after a summer program for gifted kids that was held at the university. Fighting games were weird curiosities: colorful characters equipped with secret moves in fanciful stages. The fighting games I remember are odd ones: Battle Beast, from a PC Gamer demo disk, or the inexplicable Golden Axe: The Duel. And I definitely remember Marvel vs. Capcom.

Crossover

Marvel vs. Capcom is a crossover between characters taken from each company’s stable of games and comics. These were characters I recognized from elsewhere: characters from the cheaply-animated X-Men cartoon (Gambit! so cool!) and the main character of Mega Man 3 (which I played at an elementary school after-school program). It also had glimpses into unknown works: what on earth is a Captain Commando, and who is this mysterious Morrigan (from something called Darkstalkers, I was told)? The animation was beautiful and the game was fun even though I was terrible at it.

A few years ago, I gained access to a copy of Marvel vs. Capcom 3. Ostensibly, it uses the same premise, but the years had not been kind to my perception of the series’s development. It draws an inexplicable three fighters from Resident Evil, the game with the most boring characters ever conceived. It includes characters from Okami and Viewtiful Joe, which is ridiculous albeit creative. It includes Zero instead of Mega Man. It has Nolan North cosplaying as Deadpool.

Tag Team

My time at the summer program at ASU was fun and challenging. I took my first game development class there. But my life at the time wasn’t amazing. I had things better than a lot of people, but I had emotional and social problems that took me years to understand and deal with, hurting people along the way. That arcade, and Marvel vs. Capcom, was an escape, a place where I didn’t feel surrounded by hostility or self-loathing. I had friends at school, good friends, but they always felt like the rare exceptions that were willing to spend time with me. Things were different at the summer program, where the shared identity of “gifted kid” let me accept friendship at face value.

Years later, I played MvC3 while part of a polyamorous triad that I’ve written a bit about elsewhere. It wasn’t a good look. It proved toxic for all three of us. MvC3 was another sort of escape, a thing for us to do together that was theoretically low-pressure and safe from meaningful conflict. I haven’t played much of it.

MvC3 feels like MvC writ large. The pixelly art of the original is replaced with higher-fidelity 3D models that ultimately lack character. Instead of two members for your tag team, you have three. There’s a forgettable story.

It’s fine. The game is fine.

Backstory

Works like the Marvel vs. Capcom series are virtually unique to comic books and games. It’s exceedingly rare to see a crossover novel or television show. But comic books mix and match their characters with wild abandon, even between companies on occasion. And video games are full of weird crossovers: the various Capcom Vs. series, the Smash Brothers series, the unrepentant cameos that appear time and again, regardless of how poorly one character might fit in another game. How many games contain a playable Ezio Auditore, or at the very least his pointy hood?

Marvel vs. Capcom is a product of its environment. Without the background that spawned it, it would not exist.

This article was commissioned by a patron. To support my work, sign up for my Patreon and help me continue producing writing like this.