Complicity is the most important distinguishing feature of games.

Other media still requires your interaction. You choose the order in which to experience a series (broadcast or DVD order of Firefly? publication or chronological order of Narnia?), the way in which you experience a painting or sculpture (from a distance? different angles? different lighting?), or how you experience a play (what cast? what seat? do you read it first? do you watch it staged at all?).

However, only in games do your actions involve a complicity with the diegetic1 events of the game. When you choose not to watch an episode of Supernatural, you do not absolve yourself of the injuries the Winchesters experience. There is no way to examine Guernica which makes you responsible for the depicted atrocity. Listening to the 1812 Overture on MP3 rather than live may save on real-world gunpowder but does not inform your relationship to Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, fictional or historic.

However, when you choose to punch a reporter in the Mass Effect series, your action (with the assistance of the games’ developers) causes an assault on a (fictional) civilian member of the press. You probably feel emotions as a result of this that are related to that complicity: “personal pride” or “embarrassment”, not simply “just satisfaction” or “disappointment.” The experience of consuming this work is different because it requires your active participation: pressing a button to trigger an action, not just turning a page to advance the narration.

This responsibility the player bears for the events of the game is what I’m calling complicity.

But what about when a game makes you complicit in something that you do not want, where you do not have a choice in the matter? I’ve written before about the tragedy in the ending of Prince of Persia (2008), but the most apropos in-game examination of this is the “Museum Ending” of The Stanley Parable.

Created For You Long in Advance

The Stanley Parable2 features the titular player character being guided by an unseen Narrator through a physically- and narratively-branching absurdist story, steered by more-or-less blatant binary player choices. In one ending3, Stanley is given a respite from certain death when a meta-Narrator takes over, commenting on the illusion of control the game presents and showing “behind-the-scenes” material, before returning Stanley to the previous deathtrap and entreating:

But listen to me. You can still save these two. You can stop the program before they both fail.

Press “escape” and press “quit.” There’s no other way to beat this game.

As long as you move forward, you’ll be walking someone else’s path. Stop now, and it’ll be your only true choice.

Whatever you do, choose it! Don’t let time choose for you! Don’t let time choose for you!

And if you don’t quit before the end of her narration, Stanley is killed.

This ending frames all other choices in the game as “false,” saying, “When every path you can walk has been created for you long in advance, death becomes meaningless, making life the same. ” In this view, you are complicit in the choices Stanley makes, but you have no agency in them. You are only selecting from a menu of actions not of your own creation… but this, paradoxically, makes you responsible for interacting at all with this broken system.

Is the choice to end the game at any time a “true” choice? Is it a choice that you are complicit in, within the “magic circle” that circumscribes the play space, or is it a choice akin to closing a book before the end and imagining that it preserves the fictional world in stasis?4

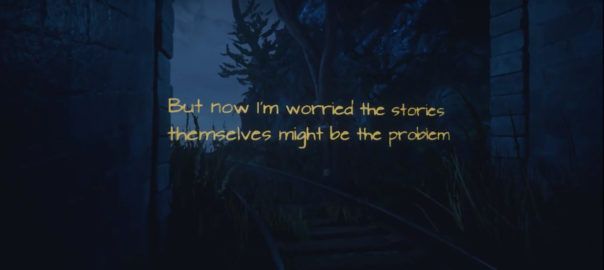

The Stories Themselves Might Be the Problem

What Remains of Edith Finch, by Giant Sparrow, has the player embody Edith, the youngest of a family that suffers from a “curse” that purportedly causes the dramatic death of every member. You explore the now-abandoned and implausibly-architected Finch home, uncovering accounts of these deaths. Each time you find one, you then reenact the final moments of each character.

These reenactments are tragic and brutal. Many of them involve children and require you to take action that you know will lead to their deaths. While this is thematically consistent — the game explores concepts of fatalism, death-seeking, and self-defeating self-narratives — it is a traumatic experience for many players. The game arguably avoids becoming exploitative by couching the reenactments in fantasy, but the fact remains that the player must become repeatedly and deliberately complicit in the death of a child and experience what is, on its surface, their ensuing dying fantasy.

This is a story in which the player is the villain. In any interpretation, you are repeatedly taking on the role of the cause of the characters’ demise, whether that is a literal curse, a familial disposition toward risk, or just a dangerous framing of the family’s narrative. There is no opportunity to continue experiencing the game’s story without being complicit in death.

The fact that the deaths have “already occurred” in the past of the game’s central narrative thread is immaterial, as is the fact that the player, after the first death or two, is sufficiently warned what they’re getting into. These facts don’t change the traumatic experience of embodying and enabling each death.

When I played Edith Finch, I found the experience tragic and harrowing but ultimately cathartic; my complicity in death felt worth it given the concepts and aesthetic journey it allowed me to explore. However, this experience is (of course) not universal.

Writer and sustainable technologist Aurynn Shaw writes about Edith Finch in her piece “On Forced Complicity in Games.”

What Remains of Edith Finch was rated as one of the best games of 2017, but I’m not going to remember the story or the themes or the writing. None of that touched me, because of the alienation of discomfort. All I remember is that discomfort. All I will remember is that discomfort.

Chances are, if you create works, you want those works to be read, understood, and retained by others. Traumatic emotional experiences, such as being complicit in the death of a (fictional) child, tend to override memory and perspective. To require a player be complicit in deliberately uncomfortable acts in order to experience your game is to alienate and exclude a player that might otherwise be a prime audience for your work.

There will always be (and should always be!) games which challenge the player emotionally and force them to be complicit in tragedy. However, doing so not only gives players a deeply unpleasant experience, but also undermines the retention of that experience by those most affected. The people who most strongly feel their own complicity in the tragedy of the game are those most likely to only remember that unpleasantness instead of the underlying message or story of the work.

This is yet another reason why considering choice, agency, and accessibility is vital to the game design process. If Edith Finch had allowed me to skip the reminiscence of the tragic death of children, it would have been less effective for me; that discomfort was acceptable and essential to my appreciation of the work. However, it was actively disruptive to Shaw’s appreciation of the game.

Design is always a task of considering a diverse audience and making tradeoffs. Designers must consider how they force their players to be complicit in the events of the game.

Because the designer is complicit in however the game affects those who play it.