Dr. Langeskov, The Tiger and The Terribly Cursed Emerald: A Whirlwind Heist is a weird little free game that’s a whole lot like the demo to The Stanley Parable, which was designed by the same person. No, not Davey Wreden, the creator of the original mod; his followup game is The Beginner’s Guide, a first-person experiment in form that explores the creative process as relates to video games, inspired in part by the impostor syndrome triggered by unexpected popularity. Heist is designed by William Pugh, who worked with Wreden on the standalone remastering of Stanley, and this followup is a first-person experiment in form that explores the creative process as relates to video games, inspired in part by the impostor syndrome triggered by unexpected popularity.

Dr. Langeskov, The Tiger and The Terribly Cursed Emerald: A Whirlwind Heist is a weird little free game that’s a whole lot like the demo to The Stanley Parable, which was designed by the same person. No, not Davey Wreden, the creator of the original mod; his followup game is The Beginner’s Guide, a first-person experiment in form that explores the creative process as relates to video games, inspired in part by the impostor syndrome triggered by unexpected popularity. Heist is designed by William Pugh, who worked with Wreden on the standalone remastering of Stanley, and this followup is a first-person experiment in form that explores the creative process as relates to video games, inspired in part by the impostor syndrome triggered by unexpected popularity.

I need to write more about The Beginner’s Guide.

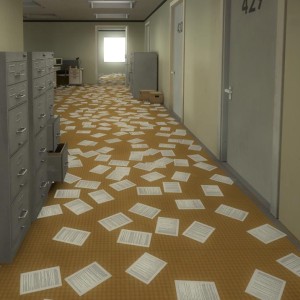

Pugh, who is probably responsible for Stanley‘s visual polish and environmental cleverness, uses the same premise here as that game’s demo, even beginning with the same joke of showing what initially seems to be a title screen but turns out to be a poster on the wall. A Whirlwind Heist follows the earlier game almost beat for beat: a narrator admits that they’re unable to let you play the game immediately, but offers you a behind-the-scenes tour, there’s jokes about video game concepts being real-world machines operated by people, and finally you never get to play the game that you were promised. They’re even roughly the same length.

The difference here is that you’re asked to be complicit in the inept “live” staging of an underfunded game, operating behind the scenes and not getting to do any of the cool stuff that the real player gets to do. The narrator is harried and unsure, unlike Stanley‘s pompous, commanding narrator. This is a funnier game than Stanley because it places you in the role of antagonist.

Most any action you choose to take contrary to instructions is met not with a tut-tut but with a shriek of frustration. The game sets up a joke for you and lets you knock it out of the park, instead of making you the butt of the laugh. The jokes in this game are like the “speak button” joke in Portal 2 or Face McShooty in Borderlands 2. You are the comic demon sent to make the narrator’s life hell, and they seem to deserve it.

I love to see games that give you a short experience, not asking for any big choices or presenting any challenge. Just giving you a little vignette of humor or pathos and then signing off. Gravity Bone, “Room of 1000 Snakes,” A Whirlwind Heist, and the like are not using the full potential of the medium; they don’t provide interactive storytelling and the joy of mastery over deep rules systems. But I love them so much.