I’ve been playing a lot of Left 4 Dead lately. I got it in the recent weekend sale, and I can say with confidence that it’s the best co-op experience I’ve ever had. It’s got the typical Valve polish, it’s fun and funny, and the experience of finding, playing, and reminiscing about a play session is a complete joy. There’s an incredible amount to talk about here, from the way the setting is introduced through wall scrawlings to the way the game teaches you how to play. I’d love to see Richard Terrell do an article about the tactics and interplay of L4D. But I’m primarily a story guy, so I’m going to talk about the story.

Left 4 Dead is George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead as told by Samuel Beckett.

Waiting for Godot is a play where nothing happens. Two much-abused innocents, Vladimir and Estragon, hang around a tree in the middle of a wasteland waiting for the titular Godot to somehow save them. Godot never comes. As they wait, Didi and Gogo discuss philosophy, suicide, and hunger, and are visited each day by a rich man named Pozzo and his slave Lucky. At the end of each of the two acts, a boy comes to announce that Godot will surely come tomorrow. It becomes clear that the pair have been waiting forever, and that the events of the play repeat eternally.

Left 4 Dead is a game where quite a bit happens. Four ragged “Survivors,” Louis, Zoey, Bill, and Francis, battle their way through zombie-infested, decayed environments in an attempt to get to a place of rescue. As they travel, the Survivors encounter five Special Infected: strange mutations of the regular zombies dubbed the Boomer, the Smoker, the Hunter, the Tank, and the Witch. Each campaign ends with the Survivors being rescued, but each begins with no mention of a previous escape. One gets the feeling that these Survivors have been surviving for a long time, and will do so forever.

The Survivors show signs of a life before the pandemic. Louis was an IT professional, Zoey a college student, Bill a Vietnam vet, and Francis a biker. Their clothing is messy and their faces are dirty, implying that it’s been a while since the rise of the infection. They’ve been fighting together for some time before the start of the campaign; the opening cutscene depicts their discovery of the Special Infected, and it’s clear that they have formed a close group at that point. Bill and Francis have a friendly rivalry, and they all look out for each other.

An indeterminate period passes between this cutscene and the start of a campaign, long enough for the Survivors to nickname the Specials, recognize their distinctive sounds, and learn how to fight them. A Survivor calls out warnings when a Special is nearby, and will occasionally provide reminders to, say, turn off flashlights when the Witch is around. The survivors have become an efficient team; they’ve learned to announce when they reload, call out useful weapons, and help each other in times of vulnerability.

But there’s no real hope for the Survivors. Each trip through a campaign is different, but it begins with them knee-deep in the undead, and ends with them escaping to an uncertain future. We never see the Survivors truly safe. Between chapters, they rest in Safe Rooms, but they can’t hide there forever. Most unsettlingly, there are signs that the Survivors themselves remember doing all this before. Each of them is familiar with the territory, pointing out upcoming safehouses. During campaign intros, a Survivor will sometimes mention that they “heard” evacuations were happening at a location, but not who they heard it from.

Even death is no escape for a Survivor. A dead Survivor will appear at the next safehouse, but they will also find themselves trapped in “rescue closets,” waiting to be discovered by the others. They seem to have memories of the others while trapped; for example, Zoey will sometimes call out, “Guys? Guys! I’m over here!” when in a closet.

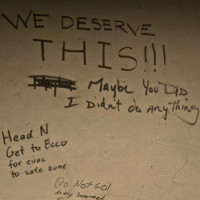

Of course, many of these creepy details are motivated by gameplay requirements; permanent death would hardly be fun, and campaigns need to be played multiple times. However, other things also suggest this hopeless eternity. The “Death Toll” campaign includes graffiti saying “Exodus 9:15,” a Bible verse describing divine punishment through pestilence, and contains a section where a church provides little refuge. “Dead Air” contains numerous spraypainted messages that “God Is Dead.” No other uninfected humans are ever seen throughout the game; only their voices are heard over radios and through doors.

The Special Infected are unsettling, as well. The Boomer is bloated and overweight, evoking thoughts of decadence and indulgence. The Smoker is thin and clearly unwell, in keeping with its name. The hooded Hunter suggests various undesirables of uninfected culture, from the Unabomber to rebellious skaters. The Tank is an embodiment of artificial, steroidal muscle, and the Witch is defined by unrestrained emotion. These zombies are not alien; they suffer from maladies that are all-too-human, which is what makes them so disturbing. A case could be made that these are the incarnations of modern-day Deadly Sins, populating the Survivor’s eternal hell.

Like in Waiting for Godot, the Survivors of Left 4 Dead are trapped in a never-ending cycle, figurative or literal, of constant struggle. There is no rest, and no hope of permanent salvation. However, like Didi and Gogo, the Survivors keep moving because of the only bright aspects of their existence: humor, friendship, and the hope of escape.

Interesting points all. I only played the freebie L4D so far, so I got to tour No Mercy and play as infected in Dead Air, but that’s about it. I love Valve’s storytelling technique, and especially the chatter, but yeah, it does seem a little like the Zombie Apocalypse with Respawn. I thought that maybe the four characters represent a broader range of survivors, and their friendship and camaraderie represents a similar bond between wider groups of people (or just different people). It’d be nice to have different characters, although only superficially.

samuel?

Yes, Samuel Beckett, not William. o_o What was I thinking? I’ve fixed it. Thanks.

I really like the comparison you make between Left 4 Dead and Waiting for Godot, especially because I always get a kick when artists play with the idea that characters within their work might be, if only fleetingly, aware of the artificial way in which they’re forced to play out a pre-defined role within a pre-defined scenario.

Still, I don’t think there’s that much in L4D to merit such a cool interpretation, at least as far as characterisation is concerned. What does strike me as interesting is the effect the random and scaling elements within Left 4 Dead have on your experience of the game. Because it’s very difficult to ‘master’ the title in the same way that you might master, say, Super Mario Bros, you get the sense that you’re not in control of the action, but merely reacting to it as best you can. The fact that you work in a team further reduces your belief in the individual agency of your character to have any impact on the larger game world.

Mind you, as far as metatheatre goes, I’d reckon a crossover like Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Left 4 Dead would make for a more interesting title, heh.

Wow! That was cool ^^

I played L4D ones or twice but I just thought it to be the usual zombie shooting game (which it is). But I never questioned the endless repeating.

I heard of the Godot play before and I found it intriguing how you connected them both.

Also the fact that the special zombies refer to nowadays ‘sins’ would never have crossed my mind, but now that you made the connection it sounds really logical.

Thanks! Cool review/thingy ^^

YES. I really love L4D, though I think the campaign is worse than survival and versus though.

Schwa? But survival is just rush after rush of zomblies, without any context. The campaign, at least, has some continuity.

This is an interesting read on the game. As far as the survivors pointing out safe houses, they only do that once they’ve seen the spray painted symbol indicating that there is one nearby. Similarly, they all know details about the environments, like Louis mentioning that the subway is the easiest way to Mercy Hospital, presumably because they lived in these areas before the outbreak.

However, the idea of sin and punishment ties into the gameplay nicely. There is a constant illusion that the dangers of the game are avoidable, and thus it becomes the players fault that get hurt in it. Things that can be avoided in theory: car alarms, Hunter pounces can be broken midair with a melee attack, Smokers give two or three seconds after they grab you to aim and fire to free yourself, Boomers can only attack up close, Witches can be snuck past or crowned, and Tanks can be outrun (but only if you’ve avoided the other dangers and kept your health up). Even the zombies take a moment to start striking you after stumbling up. There isn’t a single attack in the game that is unavoidable if reacted to quickly enough, which is quite a design feat in it’s own right. In practice of course there’s almost always too much chaos for this to work out perfectly, and people trying to act as lone wolves are especially susceptible to being ambushed and killed. More than this, because of the Director, cowardice and a slow pace is punished by extra waves, while hubris and rushing ahead is equally dangerous because the player then gets caught with no cover when the Horde shows up.

I’ll take this a little farther and note that the game is set up like a pilgrimage. You travel from safe house to safe house, all of which have had countless survivors already come through, marking the path and showing the way ahead to a predetermined final location that holds the promise of salvation. The four characters are always seemingly the final ones leaving the city, even the helicopter pilot remarks that it’s his last run for the day. Considering that the chapters of the game were initially intended to link together, stringing one failed escape attempt after another, the seeming purgatory vibe of it isn’t so misplaced. Perhaps the answer isn’t that they are the last ones trying to leave after having dawdled too long, but instead that it is truly impossible to leave and they are simply the ones who have survived the longest on a cyclical journey through the ruined city.

I have this uncontrollable urge to correct things in this analysis. Stupid, little things which probably have little bearing on the actual analysis here, but they are going to keep bugging me unless I say them.

The opening cutscene of the game has the survivors climbing onto a rooftop. The No Mercy campaign is considered to be the first scenario, and I believe a closer look will show that the survivors begin this campaign on that very same rooftop. Likewise, the developer commentary at the end of the campaign reveals that in the original cut, the helicopter pilot at the finale mentions that he has been feeling strange, and the second campaign would have begun at the site of the crashed helicopter. In the end, Valve chose to cut those connecting details out, because referring explicitly to the unsuccessful escape would cheapen the sense of accomplishment players feel. Still, going through the campaigns in order, there is a definite progression of moving out of the city, through the suburbs and into the rural countryside. I believe the game can be thought of as a cohesive sequence of events from opening cutscene to cornfield shootout, not a disjointed set of repetitive misadventures. In this fashion the story is more like that of the episodic half-life sequels and not some ever-repeating purgatory. Future expansions could easily be made to continue this single narrative, rather than simply be new scenarios.

The character’s sudden knowledge of the nuances of witch behavior is a little harder to explain in context though. And I don’t even want to *think* about explaining the ability to magically return to life in nearby closets.

That’s the thing about the cutscene-rooftop connection. Between the end of the cutscene and the beginning of No Mercy, the Survivors somehow learn the nuances of Special Infected behavior. At the very least, they spent several days on the rooftop watching the horde without getting particularly injured by passing Hunters.

Valve’s original plan was to have the stories connected, and there’s a sort of narrative progression across the campaigns, but they’re still disjointed enough that those connections are no longer there. Any rationale for the sequence concept needs to explain how the Survivors lose out on their escape plan. Why does a fully-fueled plane land again in the same state (as seen by maps) without crashing badly enough to hurt the Survivors? Why would the boat from Death Toll land in what is evidently the Infected, burning city of Dead Air? And so on. Even if they are connected, there is enough vagueness and contradiction to make the sequence fuzzy and odd.

…off the top of my head? a last minute hunter attack, or even that last tank nobody sticks around to kill, ruptures a fuel line on the plane, forcing an emergency landing in which the nose of the plane is crumpled, but the cargo area is left more or less intact. And the boat runs aground on some submerged debris, possibly even springing a leak.

The scariest thought of all, perhaps is that the cycle is not infinite, that it *does* have a clear, definite ending: The Last Stand.

Now you’re bumming me out, man.

The No Mercy campaign starts right after the main cutscene. If you look on the side of the building, the fire escape is torn off. Also, if you pay close attention in the cutscene, you can see the tarp on the roof.

The No Mercy campaign definitely starts in the same location as the cutscene ends. However, it’s unclear how much time has passed. In the cutscene, the Survivors are ignorant about the Special Infected, but at the beginning of the campaign, they are knowledgeable enough to use nicknames and recognize the Specials by their sounds.

Easily the best video game article I’ve read in a very long time. It’s connections like this that are proof (to me) that gaming IS more than empty entertainment (to some) and that this is a viable medium for artistic expression.

Well written!

Interesting article. I want to see that play now.

I wish I had a PC that could run Valve games well. Maybe I could go to a lan center, but that’s kind of expensive.

I’m planning on taking another look at co-op game design of RE5 mercenaries mode and hopefully some L4D.

I always forget that L4D is on the 360 as well. Maybe if Microsoft/Valve wanted to send me a copy of L4D to review (or something) I could magically get my hands on it and put some time into it.

waiting for godot is such a boring existentialism play. i had to read it for english 101. it was a good example to what existentialism is all about, but honestly, it’s a total waste of time reading it.

I respectfully disagree.

One thing to correct: you DO see another human in the game. When you reach the helicopter in the rooftop of No Mercy, the pilot is sitting on his seat and you can clearly see him, although you probably need to know he’s there because the seat covers him. You need to get closer to the door opposite to the helipad (don’t worry about falling, a conveniently placed invisible barrier blocks you).

Anyway, interesting post.